Waiting for

2021, Color video with sound (4K)

33 Hours 19 Minutes 26 Seconds

Narration, Edit & Direction: Yuki Harada

CGI Design & Animation: SUNJUNJIE

Reserch & Sound Edit: Akane Tanaka

Cooperation: Katsura Muramatsu, Kanta Nishio

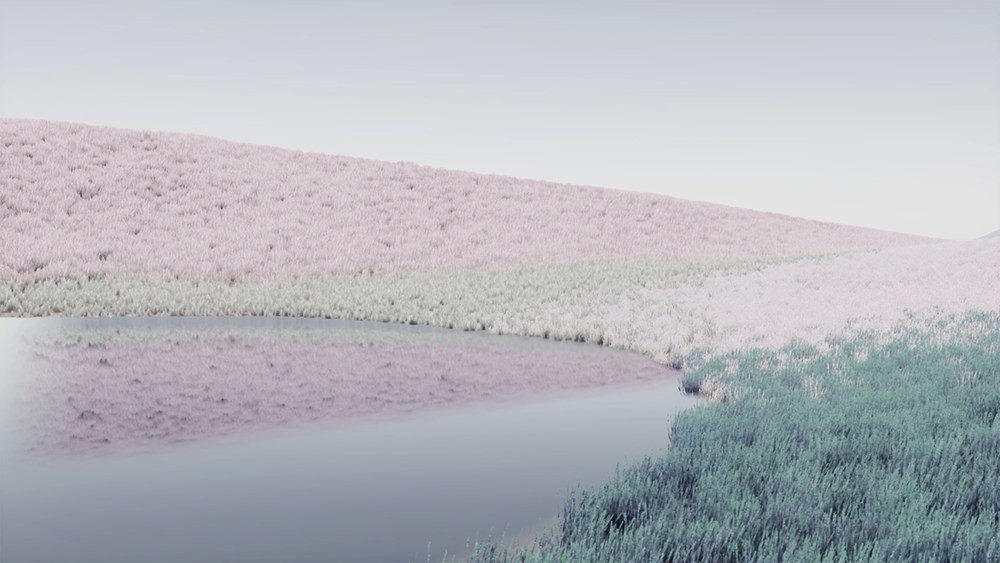

This work is an animation/narration performance piece created using the computer-generated imagery (CGI) technology used in game production.

The three spaces, created from model images of the earth one million years ago and one million years from now, spread out endlessly like an open-world game, and a virtual camera wanders around them endlessly.

What reverberates throughout the work is the names of all the animals that exist on the earth, which the artist himself recites over the course of 33 hours and 19 minutes. The common names of animals, which are composed of their characteristics and the names of the places where they live, are in themselves like an “ark” that conveys the relationship between humans and nature.

The act of calling out the names of living things that exist on the earth (=this shore) while immersing oneself in a world that reminds us of somewhere other than here (=the other shore) creates a new “landscape”, rising up between the other world and this world.

Waiting for

2021年、ヴィデオ(4K、カラー、サウンド)

33時間19分26秒

朗読・編集・監督:原田裕規

CGIデザイン・アニメーション:SUNJUNJIE

リサーチ・音響編集:田中茜

協力:村松桂、西尾完太

本作は、ゲーム製作などに使用されるCGI(Computer-generated imagery)の技術を用いてつくられた、CGアニメーション/ナレーション・パフォーマンス作品である。

100万年前、あるいは100万年後の地球をイメージして生成された3つの空間は、オープンワールドゲームのようにどこまでも広がり、その中を仮想のカメラがあてどなく彷徨っている。

そこに響きわたるのは、作家自身が33時間19分にわたって朗読し続けた、地球上に現存する全ての動物の名前である。人から見た特徴や地名などによって構成される動物の俗名は、それ自体が人と自然の関係性を伝える「箱舟」のような存在だ。

ここではないどこか(=彼岸)を思わせる世界に没入しながら、この地球(=此岸)に存在する生き物の名前をいつまでも呼び続けるという行為は、あの世とこの世の間にある新たな「風景」を立ち上がらせている。

Artist’s comment

I’ d been wondering for some time what exactly constitutes a contemporary “landscape.”

Traditional landscape paintings more often than not depict an elevated overview. These days though, merely fixing the viewpoint in a high place is unlikely to give an overview of the time frame we know as “contemporary.”

So where should we set our viewpoint? My attempt to answer this was 2021’s Waiting for, with its recitation of all members of the animal kingdom (including homo sapiens) currently found on earth, and visualizations of scenes without various of these, a million years in the past, and future.

Scraping together material from a number of sources, and seeking advice from academic societies and research institutions, I compiled a huge list of common animal names in Japanese and English. Having managed to complete this list, I realized that it would take at least thirty hours to read aloud the more than 20,000 names on it.

Initially I imagined that in order to create a single “viewpoint” covering all of these names, I would have to read them non-stop without pausing. But when I actually started trying to recite them, I failed several times, due to fatigue, drowsiness, and misreading, so in the end decided to divide the reading into two sound recordings of and twenty ten hours each to make the work.

My decision was prompted by having been powerfully reminded of the limits of the human body.

In this recitation, like water spilling over from a full glass, a surfeit of information and the physical strain of the exercise combined to make it constantly unmanageable in some way or another, for both performer and spectator. It was in this spilled-over state that I felt something arise we mere humans can only guess at, something worthy of the name, “landscape.”

作家によるコメント

現代の「風景」はどんなものだろうかとずっと考えていた。伝統的な風景画は、高所から見下ろした構図で描かれることが多い。しかし今となっては、単に高所に視点を設定しただけでは、「現代」という時代を俯瞰することはできないだろう。

それでは、その視点はどこに設定されるべきだろうか。そのために試みたことが、《Waiting for》(2021)における「地球上に存在する全ての動物の朗読」と「あらゆる動物がいない光景(=100万年前/後の光景)」のビジュアライズだった。

まずはいくつもの資料をかき集めて、学会や研究機関にも確認を仰ぎながら、膨大な動物の和英俗名をリスト化する作業から始めた。なんとか完成させた2万種以上の俗名リストの朗読には、少なくとも30時間以上を要することもわかった。

それらを俯瞰するひとつの「視点」をつくるために、当初は切れ目なくノンストップで読み上げを行う必要があると考えていた。しかし実際に朗読してみると、疲労、眠気、読み間違えなどにより、朗読は何度も失敗に終わり、最終的には、20時間と10時間の2回にわけて収録した音声を作品にすることにした。

そう決断したのは、このときに人間の身体の有限性について改めて強く実感させられたからだった。この朗読では、まるでコップの水が溢れるように、多すぎる情報や身体的な負荷など、演る者にとっても観る者にとっても、常に何かが手に余る状態が続いている。この何かが溢れた状態にこそ、ちっぽけな人間には推し量ることのできない「風景」と呼ぶべき何かが立ち上がるのを実感した。

「アペルト14 原田裕規 Waiting for」(金沢21世紀美術館、2021年)ハンドアウトより[JP / EN]

Anticipating a Largely Touch-less World: On Yuki Harada’s Waiting For

Hiroki Yamamoto (Cultural Studies Scholar, Artist)

The word “apocalypse,” meaning “revelation” in Christian religious contexts, is also used when talking about the “end of the world” or “catastrophe.” Sergio Fava has pointed out that “apocalyptic narratives” are found throughout human history, and argues that the term can be broadly applied to events leading to “total destruction or just overwhelming transformation of the planetary ability to sustain human life [1].” As Fava also emphasizes, especially since the 2000s, the contemporary apocalypse is frequently referred to in connection with climate change.

Linked to this, the geological term “Anthropocene” has recently become the focus of attention in humanistic and scientific fields alike, including philosophy, economics, and political science. This surge of interest in the Anthropocene as a term that implies the unignorable impact of human activities on the global environment, is not limited to academia. A symbolic example in Japan is Hitoshinsei no “Shihonron” “Capital” of the Anthropocene by economic thinker Kohei Saito. In this book, which sold exceptionally well for an academic publication, Saito attempts to offer an effective prescription for tackling the climate crisis by “‘discovering’ and developing a completely new aspect of Marx’s thought [2].”

In contrast, environmental historian Jason Moore proposes the concept of “Capitalocene,” based on the critical idea that “questions of capitalism, power and class, anthropocentrism, dualist framings of ‘nature’ and ‘society,’ and the role of states and empires” are “frequently bracketed by the dominant Anthropocene perspective [3].” The following perception of the current situation by political scientist Shin Chiba, who maintains that the triple crisis of “capitalism, democracy, and ecology” is becoming increasingly serious, exemplifies the “apocalyptic narrative” of our time: “The ecological crisis […] retains a certain apocalyptic dimension, namely, the relationship between humans and nature. […] Apocalyptic dimension here refers to the occurrence of unprecedented incidents that foretell the end or ruin of the human species and the world [4].”

The COVID-19 pandemic, which originated in China at the end of 2019, spurred people’s sense of urgency about the climate crisis, and awareness of the need to radically reconsider “the relationship between humans and nature at large” (sociologist Masachi Osawa) has never been stronger [5]. Furthermore, the bewildering impact of Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine since February 2022 continues as I am writing this two months later in April, leaving a great number of scholars and politicians at a loss for words at the sheer unexpectedness of the situation. With even “experts” unable to fully explain what is happening, it is natural that no one can completely deny the possibility of a nuclear war that could spell the end of the human race.

What is being generated in Waiting for, at first glance, is a virtual space completely unrelated to such real world conditions. It is a CG animation that was created by artist Yuki Harada in 2021, and exhibited in slightly modified forms at different locations including the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Kyoto Art Center, and KEN NAKAHASHI. In this work, a virtual camera moves through an artificial world modeled by the artist using 3D computer graphics, and incorporating a variety of references that transcend time and place, such as artworks by the Spanish design studio “Six N. Five,” which has produced CG images for interior advertisements and PC desktops [Fig. 1]; a landscape painting by German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich [Fig. 2]; and conceptual works by Yutaka Matsuzawa, the most important artist in the postwar art movement known as “Nihon Gainen-ha” (Japanese Conceptual School).

What is utterly stunning is the length of the animation. Its running time of 33 hours and 19 minutes corresponds to the time it takes Harada to recite the names of all animal species that currently inhabit the earth. Regardless of the considerable physical and mental toll this action takes on the viewer, Harada tries to maintain a calm tone and consistent intonation as he reads down the names in a matter-of-fact manner.

When I attempt to connect Waiting for to an international context, authors such as David O’Reilly and Marina Zurkow come to mind. In O’Reilly’s

Everything (2017) [Fig. 3], the player navigates through a virtual CG environment, while taking possession of various objects that exist there – animate or inanimate, from extremely large to extremely small. Similar to the hypothetical point of view in Waiting for, through the anonymous fixed point roaming around O’Reilly’s constructed universe, the participant’s perception is taken to a super-human level.

In 2001, media artist and theorist Lev Manovich published The Language of New Media, in which he attempted to describe “the language of computer media” that is emerging along with the advent of “the meta-media of the digital computer,” by using the term “new media [6].” Even twenty years later, the importance of Manovich’s argument has essentially not deteriorated. It will be a fruitful exploration to examine Harada’s Waiting for with the axis of “new media” in mind, and while linking the concept to the trends that have developed particularly in Europe and the United States.

On the other hand, looked at from an “ecological” perspective, it is interesting to contrast Waiting for with Zurkow‘s Mesocosm (Wink, Texas) (2012) [Fig. 4]. The philosopher Timothy Morton, whose speculations have been focusing on the Anthropocene, and Masatake Shinohara, who introduced Morton’s philosophy to Japan, positively refer to Zurkow‘s animation piece as a sensory expression of a new vision of “nature.” It features countless butterflies and people in protective clothing, whereas only the butterflies and protective suits are colored bright yellow. The somewhat sterile atmosphere of the work, evoking a post-Covid world, substantially resonates with Waiting for.

Moreover, it might be possible to place Waiting for in the genealogy of “neo-conceptualism” as represented by contemporary artists like Seth Price, Ryan Gander, and Martin Creed, all of whom are popular in Japan. This hypothesis is complemented by the fact that Harada has investigated in detail the works of Matsuzawa, one of the pioneers of Conceptual Art in Japan, during the making of Waiting for. The result is a work that is quite open to numerous circuits that are connected to global and local contexts alike, and that entails diverse possible interpretation and further development.

When I described Waiting for as seemingly “unrelated to such real world conditions,” by “such” I meant to refer to the recent circumstances with multiple, frequently occurring crises, as discussed at the beginning of this article.

Indeed, Waiting for is an odd world in which “nothing special happens,” yet it transgresses the boundary between the artificial and the natural, and is filled with something akin to a tranquil rustling, like a peaceful ripple that forebodes a thunderous tectonic shift. This, however, is not to say that Harada specifically predicted the current situation. Needless to say, he is an artist, not a prophet.

The “sense of foreboding” described above, I felt, stems from the peculiar tension in Waiting for: between the primordial world from which humans came, and the apocalyptic world we might find at the destination of scientific rationality that gave us nuclear and biological weapons, or of intensifying ethnic and religious conflicts. In this sense, Waiting for expresses both a sense of “before” something happens, and “after” something happened. In Harada’s video, a world that encompasses on a large scale the past and the future, his act of endlessly reciting the names of creatures seems like a call from outside history, a place divorced from the timescale of living creatures (naturally including humans), to the countless life forms that once enjoyed (or will enjoy) life there, and then to the absence of those life forms, in order to confirm every single one of them – and their very absence – one by one.

What awaits us is an extremely unpredictable world. Since the advent of postmodern thought, this idea has been a cliché. However, in fact, more than a quarter century after it was first articulated, the degree of unpredictability of the world is undoubtedly increasing.

In addition to the rapid development of digital technology, those of us living through the current pandemic have avoided communication that involves contact, and “density” has become a taboo. While there have been positive changes brought about by such circumstances, it is also true that the coronavirus has eradicated dense contact, and deprived the world of the roughness and vividness of “touch.” With the atmosphere of a sterile room, Harada’s Waiting for partially indicates such a world without touch. The viewer is constantly suspended within a plateau between a sense of “before” and “after” something happens, and such is the inner feeling that we have no choice but to confront an unpredictable future with. Yuki Harada’s Waiting for presents a model of the world to come (or has already arrived) – without falling into the simple dichotomy of a utopia colored with optimism, and a dystopia filled with pessimism.

[1] Sergio Fava, Environmental Apocalypse in Science and Art: Designing Nightmares, Routledge, 2015, 1.

[2] Kohei Saito, Hitoshinsei no “Shihonron” [“Capital” of the Anthropocene], Shueisha, 2020, 7, my translation.

[3] Jason W. Moore, “Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism,” Jason W. Moore (ed.) Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. PM Press, 2016, 5.

[4] Shin Chiba, Shihonshugi, demokurashi, ekoroji: Kiki no Jidai no Toppako o Motomete [Capitalism, Democracy, and Ecology: In Search of a “Breakthrough” in the Time of Crisis], Chikuma Shobo, 2022, 25, my translation.

[5] Masachi Osawa, “Only the Impossible Can Overcome the Crisis: Solidarity, the Anthropocene, Ethics, Divine Violence,” Kawade Shobo Shinsha Henshubu (ed.) Shiso to shiteno <Shingata Koronauirusu Ka> [<The Novel Coronavirus Pandemic> as Thoughts] Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2020, 11, my translation.

[6] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, MIT Press, 2001, 6–7.

私たちを待つ手触りの希薄な世界──原田裕規の《Waiting for》に寄せて

山本浩貴(文化研究者、アーティスト)

キリスト教で「黙示」を意味する「アポカリプス(apocalypse)」は、転じて「世界の終末」や「大災害」の意に用いられる。「終末論的物語(apocalyptic narrative)」は人類の歴史を通して散見されると指摘したセルジオ・ファーヴァは、その言葉は「完全な破局、あるいは単に人間生活を維持する地球の能力の途方もない変容」に至る出来事に広く適用されるとする[1]。 ファーヴァも強調する通り、特に2000年代以降、現代の黙示録は気候変動と関連して語られることが圧倒的に多い。

それとリンクするように、近年、地質学用語である「人新世(Anthropocene)」が文理の境界を越境し、哲学・経済学・政治学などの多領域で注目されている。この言葉は、人間活動が地球環境に無視できない影響を与えるようになった時代を指し、最近の人新世への関心の高まりはアカデミアに限定されない。日本における象徴的事例を挙げれば、経済思想家・斎藤幸平による『人新世の「資本論」』(2020年)のベストセラーがある。学術書としては異例の売り上げを見せた同書で、斎藤は「マルクス思想のまったく新しい面を『発掘』し、展開する」ことを通じ、気候危機に対する有効な処方箋を提示しようとする[2]。

これに対して、環境史学者のジェイソン・ムーアは「資本新世(Capitalocene)」という概念を提唱する。その背景には、「資本主義、権力と階級、人間中心主義、「自然」と「人間」という二項対立的な枠組み、国家と帝国の役割に関する問い」が「支配的な人新世視点ではしばしば除外されている」ことへの批判がある[3]。 「資本主義・デモクラシー・エコロジー」が絡む三重の危機が深刻化していると論じる政治学者・千葉眞が記す次の現状認識は、現代における「終末論的物語」の典型を示す。「エコロジー危機は、[…]人類と自然の関係という、ある意味で黙示録的次元を保持している[…]黙示録的次元とは、人類種や世界の終末や破滅を予示する未曾有の出来事の出現を含意している[4]」。

2019年末の中国に端を発するコロナ禍が気候危機に対する人々の切迫感に拍車をかけ、「人間と自然の関係の全体」(社会学者・大澤真幸)を抜本的に再考する必要性への認知がかつてないほど高まった[5]。 さらに、2022年2月に開始されたロシアによるウクライナへの軍事侵攻は、本稿執筆中の現在(同年4月)も引き続き混迷を極め、あまりに意想外な事態に言葉を失う学者や政治家が相次いでいる。「専門家」と呼ばれる人々ですら起こっていることを十分に説明できないなか、人類の終焉を予感させる核の脅威を完全に否定できる者はいない。

《Waiting for》において生成されているのは、一見すると、こうした現実の世界情勢とは完全に切り離された仮想の空間だ。《Waiting for》は、アーティスト・原田裕規が2021年に制作し、金沢21世紀美術館、京都芸術センター、KEN NAKAHASHIなどの異なる場所を巡回する過程で微妙に形態を変えながら展示されてきたCGアニメーション作品である。この作品では、3DCGでモデリングされた人工の世界のなかを仮想のカメラが動く。この世界は、インテリア広告やPCのデスクトップに使用されるCG画像を手がけるスペインのデザインスタジオ「Six N. Five」のアートワーク【Fig.1】、ドイツ・ロマン主義絵画を代表するカスパー・ダーヴィト・フリードリヒの風景画【Fig.2】、日本概念派と称される戦後美術の動向における最重要作家・松澤宥のコンセプチュアルな作品を含む、時代や場所を超越した多彩な参照項に基づいて作家自身が創出した。

加えて、驚くべきは33時間19分というその映像の長さだ。この長さは、現在、地球上に生息する全動物種の名前を原田が読み上げるナレーションの尺に対応する。これは心身に相当な負荷のかかる行為であるが、彼は努めて冷静なトーンと一定のイントネーションを保ち、淡々とその名を呼び続ける。

《Waiting for》を海外の文脈と接続すると、デヴィッド・オライリーやマリーナ・ズルコウといった作家が比較対象として浮かぶ。オライリーの《Everything》(2017年)【Fig.3】では、作家がCGで形成した仮想世界の内部を、プレイヤーがそこに存在する様々な諸物——極大の物体から極小な物体まで、生物から非生物まで——に憑依しながら進む。《Waiting for》での仮設的視点と同様、匿名性を帯びた定点がオライリーの構築した宇宙をうろつくことを通じて、参加者の認識は人間を超越したものへ変容する。

メディア・アーティストで理論家のレフ・マノヴィッチは、2001年に『ニューメディアの言語』を上梓し、「ニューメディア」という言葉を用いて、「デジタルコンピュータというメタ媒体」の出現と同時に新たに生まれつつある「コンピューター・メディアの言語」を記述しようと試みた[6]。 20年以上が経過した現在も、その議論の重要性は本質的に劣化していない。「ニューメディア」という軸を設定して、とりわけ欧米で発展してきた傾向と結びつけながら、原田の《Waiting for》を考察することは実りある探求となるだろう。

一方、「エコロジー」の視点から《Waiting for》を眺めると、ズルコウの《Mesocosm (Wink, Texas)》(2012年)【Fig.4】との対比が興味深い。人新世にまつわる思索を深めてきた哲学者ティモシー・モートンやその日本への紹介者・篠原雅武は、このアニメーション作品を新しい「自然」のビジョンを感覚的に表現したものとして肯定的に言及する。同作には無数の蝶や防護服をまとった人々が登場し、蝶と防護服だけが鮮やかな黄色に着色されている。ポスト・コロナの世界を想起させる、どこか無菌室的な雰囲気は《Waiting for》と共鳴している。

さらに、《Waiting for》をセス・プライスやライアン・ガンダー、あるいはマーティン・クリードなど、日本でも人気の高い現代アーティストに代表される「ネオ・コンセプチュアリズム」の系譜に位置づけることも可能だ。その仮説は、原田が本作を制作するにあたり、日本におけるコンセプチュアル・アートの祖・松澤の作品を詳細に研究している事実からも補完される。このように、《Waiting for》はグローバルな文脈とローカルなそれの双方に接合する複数の回路に開かれ、多様な解釈と展開の可能性をはらむ作品である。

少し前に、「《Waiting for》において生成されるのは、一見すると、こうした現実の世界情勢とは完全に切り離された空間だ」と書いた。「こうした」とは、冒頭で論じたように、危機が多重的に頻発する昨今の世界の様相を指す。

たしかに、《Waiting for》の世界では「何事も発生しない」。しかし、人工と自然の境界線を蹂躙するその奇妙な世界には、さざ波のように静謐にうごめくざわめきの感覚が充満している。そうした感覚は、途方もない地殻変動が起こる直前の「未然感」と表現できるかもしれない。このように言うことで、原田が現在の状況を具体的に予測していたと主張したいわけではない。言うまでもないことだが、彼はアーティストであって予言者ではない。

先述した「未然感」は、人間がそこから来たような原初的世界と、核・生物兵器を生んだ科学的合理性、ないしは民族や宗教の対立が行き着く先に私たちを待つ終末的世界のいずれを描いているようにも見える、特異な緊張関係を《Waiting for》が保持していることに由来すると私は感じた。その意味で《Waiting for》は、何かが起こる前の「未然感」と、何かが起こってしまった後の「已然(いぜん)感」をともに表現する。長大な尺度で過去と未来を同時に含みもつ原田の映像世界で生き物たちの名を呼び続ける彼自身の行為はあたかも、(人間はもちろんのこと)生物のタイムスケールからも切り離された歴史の外部から、かつてそこで生を享受していた(あるいは、これからやってくる)無数の生命体を——その不在を——声に出してつぶやくことで、ひとつひとつ確かめているようにも思えてくる。

私たちを待つのは、きわめて予測不可能な世界だ。ポストモダン思想の登場以降、この考えはクリシェである。とはいえ、そうしたことが言われてから四半世紀以上が経過し、事実、世界の予測不可能性の度合いは増すばかりである。

デジタル技術の急速な発展に加え、コロナ禍を生きる私たちは接触によるコミュニケーションを忌避し、「密」は避けられるべきタブーとなった。そうした事情がもたらしたポジティブな変化もあったが、一方でコロナ禍は濃厚接触を殲滅し、世界からザラザラした「手触り」を奪ったこともたしかだ。無菌室感にあふれた原田の《Waiting for》が部分的に開示するのは、そうした手触りのない世界である。そして、そこでは鑑賞者が恒常的に、何かが起こる前の「未然感」と何かが起こってしまった後の「已然感」のあいだにある高原状態(プラトー)のなかで宙吊りにされる。私たちはつねにそうした感覚を抱えながら、見通しのできない世界と向き合っていくしかない。原田裕規の《Waiting for》は、来たるべき(あるいは、すでに到来した)世界のモデルを——オプティミズムに彩られたユートピアとペシミズムに満ちたディストピアという安易な二項対立に陥ることなく——提示している。

[1] Sergio Fava, Environmental Apocalypse in Science and Art: Designing Nightmares, Routledge, 2015, 1.

[2] 斎藤幸平『人新世の「資本論」』集英社、2020年、7頁。

[3] Jason W. Moore, “Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism”, Jason W. Moore (ed.) Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. PM Press, 2016, 5.

[4] 千葉眞『資本主義・デモクラシー・エコロジー 危機の時代の「突破口」を求めて』筑摩書房、2022年、25頁。

[5] 大澤真幸「不可能なことだけが危機をこえる 連帯・人新世・倫理・神的暴力」河出書房新社編集部(編)『思想としての〈新型コロナウイルス禍〉』河出書房新社、2020年、11頁。

[6] レフ・マノヴィッチ(堀潤之訳)『ニューメディアの言語 デジタル時代のアート、デザイン、映画』みすず書房、2013年、41–42頁。